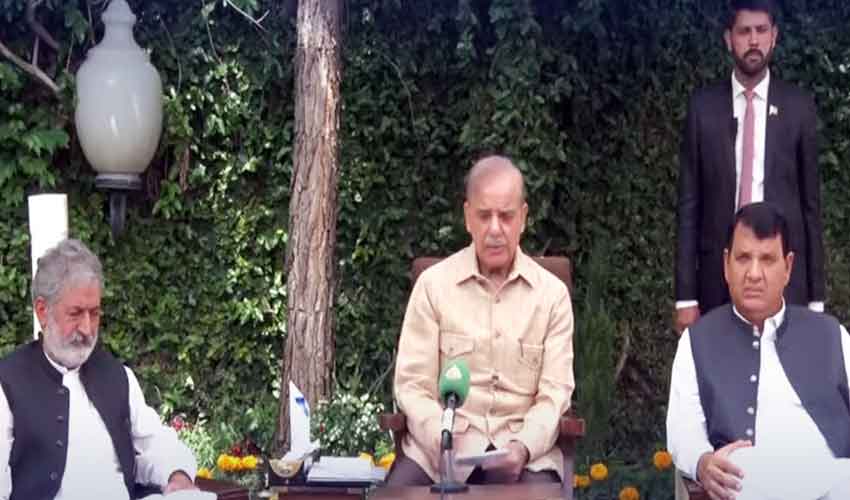

PM thanks army chief Gen Asim Munir for helping eliminate smuggling

Shehbaz says economy cannot be strengthened without ending smuggling

Shehbaz says economy cannot be strengthened without ending smuggling

Cristiano Ronaldo treats fans to snapshots of blissful moments spent with Georgina

Spox highlights report's failure to address grave humanitarian issues such as the situation in Gaza, IIOJK

Guy represented Zimbabwe in 46 Tests and 147 ODIs between 1993 and 2003

Tech giant is poised to elevate consumer experience by bringing cutting-edge AI capabilities directly to its devices

Services were discontinued by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government due to unpaid bills to internet providers.

Owner attributes her unusual colouration to biliverdin, benign bile pigment encountered in womb

PML-N's top gun laments lack of effective communication between political factions

Prince William shares glimpses of the inspiring mental health project in action

Shehbaz says economy cannot be strengthened without ending smuggling

Read all facilities to be provided in the Karachi cattle market

Court annuls ECP decision to order re-election at 12 polling stations of PB-51 Chaman constituency

Pakistan Autism Society says there are approximately 350,000 children suffering from autism disorder in country

Jacen Russell-Rowe sealed victory for Columbus

A case has been registered against the accused and the investigation is underway.

Gross domestic product increased at a 1.6% annualized rate last quarter

Cristiano Ronaldo treats fans to snapshots of blissful moments spent with Georgina

Prince William shares glimpses of the inspiring mental health project in action

Tech giant is poised to elevate consumer experience by bringing cutting-edge AI capabilities directly to its devices

It is the most recent confrontation between the police and students, who are angry over large number of people dying in Israel's war with Hamas

Since Ayesha's health is stable, she is free to go back to Pakistan

Owner attributes her unusual colouration to biliverdin, benign bile pigment encountered in womb

Implementing reporting standards 18 has its challenges, but offers long-term benefits